A question recently came up on Twitter: Did Huitzilopochtli, patron god of the Mexica, have a wife?

In fact, two major sources preserve the sacred story of how the Mexica “acquired” a “wife” for Huitzilopochtli, angering an entire nation in the process and helping to fulfill their destiny.

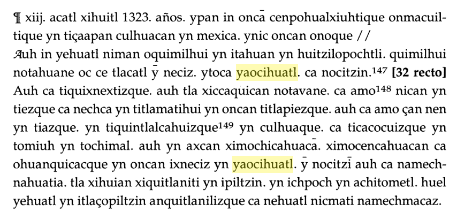

To share this often gruesome story with you, I’m going to translate the Nahuatl text contained in the Codex Chimalpahin (compiled by Nahua chronicler Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin). But I’ll also pull a couple of lines from Diego Durán’s Historia de las Indias de Nueva España (Durán was a translator of Nahuatl and drew from indigenous sources to compile his history in the mid 16th century).

THE TRANSLATION

The year 13 Reed, 1323 C.E. By then, the Mexica had spent 25 years in the Tīzaāpan region of the kingdom of Cōlhuahcān.

Huitzilopochtli then spoke to the elders, saying, “O Fathers, another will arrive. Her name is Yaocihuatl [War Woman]. She is my grandmother. And we will acquire her. [Note: this is a play on words, also meaning ‘we will exhibit her in public,’ usually referring to slaves.] Listen, O Fathers. It is not here we will remain; off there in the distance, we will take prisoners and keep watch. We will not go in vain, but we will escape the Colhuahqueh, lifting shield and spear. Now grow strong, get ready, for as you have heard, my grandmother Yaocihuatl will appear there. So I command you: go and ask King Achitometl for his child, his daughter. Indeed, you will ask him for his beloved daughter, for I know how I will repay you.”

Then the Mexica went and asked Achitometl for his daughter. The Mexica begged him, saying, “O Noble One, O Lord, O King! We, your grandfathers and vassals, along with all the other Mexica, beg you to concede, to give us your jewel, your precious one, your beloved daughter who is our revered grandchild. She will be taken care of there among the mountains of Tizaapan.”

[Diego Durán clarifies something at this point in the sacred story: the Mexica told the king that his daughter would reign over them as “señora de los mexicanos y mujer de su dios” — “Sovereign of the Mexica and wife of their god,” Huitzilopochtli.]

Achitometl replied, “Very well, O Mexica. Lead her away.”

Then he gave her to the Mexica. They led Achitometl’s daughter away, guiding her to Tizaapan and installing her there [as their queen].

Then Huitzilopochtli spoke, addressing the god-carriers, Priest Axollohua and Cuauhtequetzqui, also called Cuauhcoatl. He told them, “O Fathers, I command you to kill Achitometl’s daughter and peel off her skin. When that is done, one person, a priest, is to wear it.”

So then they sacrificed and flayed the princess, and a priest donned her skin.

Then Huitzilopochtli spoke: “O Fathers, please summon Achitometl.”

The Mexica went to summon him, saying, “O Lord, O Grandson, Great Personage and King! We, your vassals, must embarrass and trouble you. Your grandfathers the Mexica pay you homage. ‘Let him come to see and greet his goddess, whom we have invoked,’ they say.”

Then Achitometl said, “Very well. Let us go.”

Then Achitometl told the other lords, “Let us go to Tizaapan: the Mexica invite us to a feast.”

They answered, saying, “Very well, O King. Your Highness will be taken there.”

And then they took with them rubber, copal, paper, flowers, tobacco and what are termed “fasting foods” to make offerings to the goddess, as Achitometl had been instructed when they summoned him.

But it was not true. She was the one they had skinned.

When Achitometl arrived in Tizaapan, the Mexica came to meet him, saying, “Your Highness is fatigued [customary greeting], O Grandson, O Great Personage, O King. We your grandfathers, your vassals, make Your Highness ill [customary apology]. See, greet your revered goddess.”

He replied, “Very well, Grandfathers.” He picked up the rubber, copal, flowers, tobacco, and fasting food, spreading them out, arranging them before the false goddess, the one they had flayed. Having done so, he sacrificed quail before her.

But he could not quite see whom he had sacrificed the quail to.

Having done so, he lit the incense, and the incense ladle illuminated the priest who wore the skin. And when Achitometl could see it was his daughter, he was quite shocked. So he shouted, crying out to the other lords and his subjects, saying, “Who are these? Ah! You Colhuahqueh, do you not see? They have flayed my beloved daughter! These evil people will not remain here. We will kill them. We will annihilate them. The wicked will perish here and now!”

And with that, the war began.

Then Huitzilopochtli told the elders, “Truly, I knew of this. Now, with caution and stealth, leave this place.”

But the Colhuahqueh gave chase. They pursued the Mexica until they forced them into the water.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

THE COMMENTARY

The water the Colhuahqueh chase the Mexica into is Lake Texcoco. Huitzilopochtli will tell his people to use their shields as rafts for women and children and head to the barren, rocky isle that no Nahuas have claimed.

That’s where they see the sign. Huitzilopochtli appears as his nahual (animal double), an eagle, sitting on a cactus that springs from the rocks where the heart of Huitzilopochtli’s old enemy, his nephew Copil, landed generations ago.

I’ve noticed that many people have a mistaken impression about Tenochtitlan. They think the Mexica left Aztlan and just marched right to Lake Texoco to establish their city on the isle.

No. It took centuries. Even after they reached Anahuac (the region around the lake), the Mexica wandered and fought for generations. They ended up enslaved in Colhuacan.

In that kingdom, they were eventually freed, but made to live in the inhospitable region of Tizaapan, a rocky lava-flow close to UNAM’s main campus in modern Mexico City. After a generation of intermarriage, the Mexica-Colhua (as they called themselves) had a second exodus.

The sacrifice and flaying of King Achitometl’s daughter forced legendary Mexica chieftain Tenoch to lead his people to a new homeland, a desperate choice they might not have made otherwise. Pursued by Colhua troops, however, they had to obey Huitzilopochtli’s command.

Original Nahuatl Text: